I’ve spent more hours than I’d like to admit scratching lottery tickets in gas stations and convenience stores. Not because I thought I’d strike it rich—I’m not delusional—but because there’s something weirdly compelling about that instant gratification. You buy the ticket, you scratch it right there, and in 30 seconds you know if you’ve won. No waiting for a draw date. No checking results online. Just immediate feedback.

But let me tell you what I eventually realized: those scratch cards are basically a tax on people who don’t understand probability. And the math? It’s brutal. States aren’t running these games out of generosity. They’re running them because they’re one of the most profitable gambling operations in America.

How States Engineered the Perfect Money Machine

Here’s the thing about lottery commissions that people don’t talk about: they’re not in the business of giving away money. They’re in the business of taking it.

When a state launches a scratch card game, they control every single variable. They decide the odds, the prize structure, the number of winning tickets in circulation, everything. It’s not like a casino where the house edge is fixed at, say, 2%. States can set the house edge at whatever percentage they want.

And they want it high.

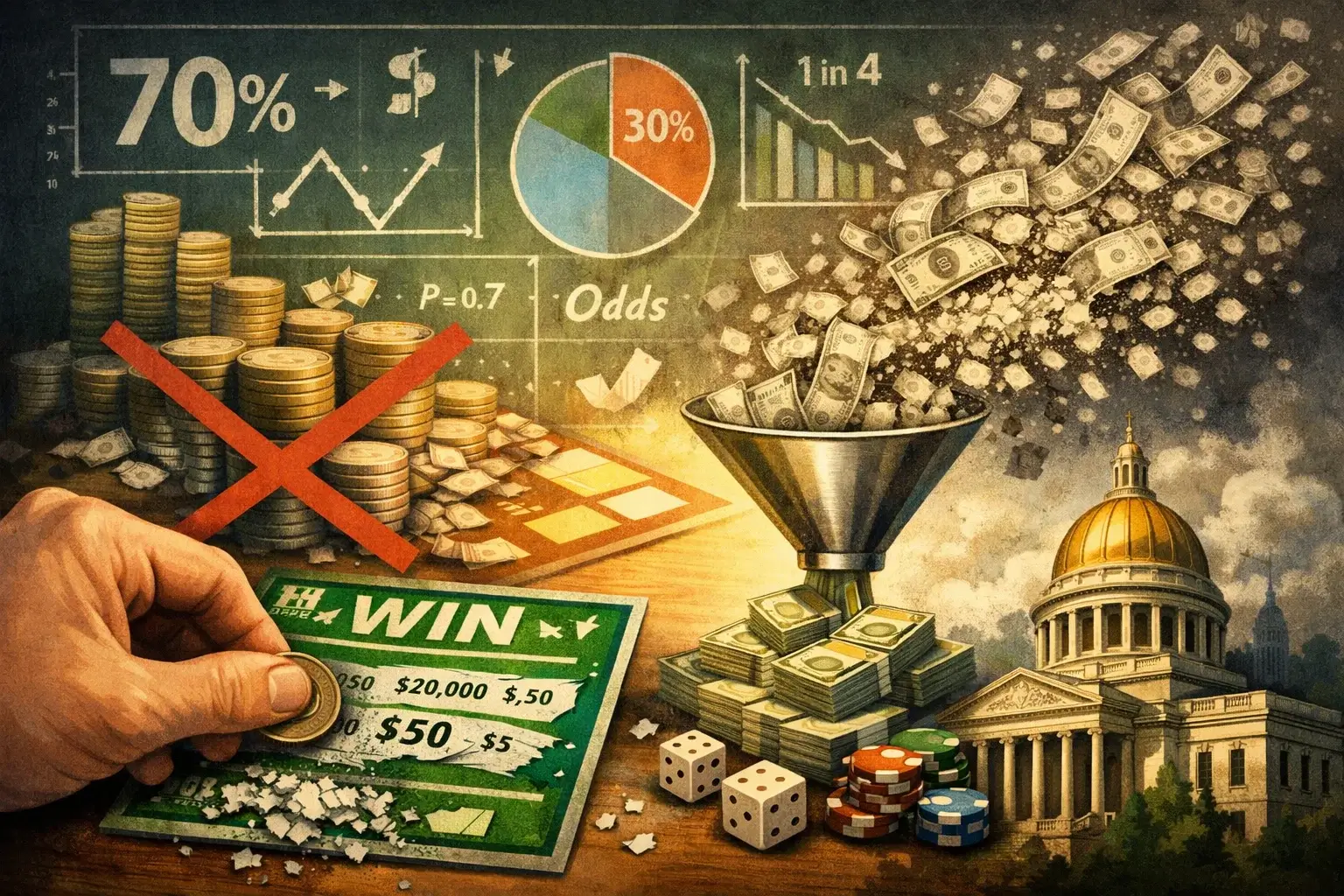

A typical scratch card game is designed so that roughly 30% of ticket revenue goes to winners. That means 70% goes to the state. We’re talking about a house edge of 70%. Think about that for a second. In a slot machine, 88-93% of money comes back to players over time. In blackjack, the house edge is around 1% if you play perfectly. But with scratch cards? You’re looking at giving up 70 cents of every dollar you spend.

The reason states can get away with this is simple: people don’t understand the math, and they don’t see the game for what it is. If you walked into a casino and a dealer offered you a game where you’d win 30 cents for every dollar you spent, you’d laugh and walk out. But put that same game in a convenient format with flashy graphics and the promise of a big jackpot, and suddenly people line up to play.

I’ve worked with lottery data, and the numbers are staggering. In 2023, Americans spent over $113 billion on lottery tickets. The payout rate across all lottery games averages around 60% nationally, but for scratch cards specifically, it’s often much lower. Some states run scratch games with 40% payout rates. That’s genuinely insane when you think about it.

What makes this worse is that states actively promote scratch games because they’re so profitable. While traditional lottery drawings like Powerball get more media attention, scratch cards generate significantly more revenue per dollar printed. A state might have $5 in Powerball ticket sales, but they’ll have $8 or $9 in scratch card sales. And the margins are incomparably better.

I’ve seen lottery commission budgets and financial reports. In many states, scratch games account for 50-60% of total lottery revenue despite representing maybe 40% of player spending. That’s because the payout rates are lower and the overhead costs are minimal. There’s no drawing infrastructure needed, no televised events, no validation process beyond having the right scanner at the retailer. It’s pure profit extraction.

The Illusion of Multiple Winning Opportunities

One of the brilliant psychological tricks of scratch card design is the multiple-play format. Instead of scratching one space and either winning or losing, most scratch cards have multiple ways to win on the same ticket. You might have three numbers to match, or you might play a game where you’re trying to beat a dealer’s hand, or there might be lucky numbers hidden throughout.

This is intentional.

When a card has five different games or play opportunities on it, your brain processes each one separately. Even if the overall payout rate is terrible, the fact that you get multiple chances to win creates this false sense of increased odds. You might lose all five games, but that felt like five gambling experiences rather than one losing ticket.

The math still works against you on every single game. Let’s say each mini-game has a 1 in 3 chance of winning something. Players think, “Well, I get three chances to win, so my odds are better.” But that’s not how probability works. The chances don’t stack in your favor. If anything, they work against you faster because you’re risking money on three separate outcomes instead of one.

I’ve had conversations with people who’ve spent $20 on a scratch card with five games and won $3 total. They’ll say things like, “Well, I won on two of them, so at least I came close.” That’s a mindset trap. You didn’t come close to anything. You lost $17. The fact that you won on two games instead of zero doesn’t change the economic reality.

The design works on something called the “near-miss” effect in gambling psychology. When you almost win but don’t, your brain interprets it as close to success. You feel like you’re getting better at the game or that the next ticket might be the one. Casino designers have studied this extensively. Near-misses create more engagement than occasional big wins because they happen frequently enough to seem meaningful.

Scratch card manufacturers know this intimately. They design tickets so that near-misses are common. You might have three numbers to match, and you get two of them. You might be playing a lucky number game and end up with a number that’s adjacent to the winning number. These aren’t accidents. They’re calculated to maximize emotional engagement without actually paying out money.

What’s particularly insidious is that scratching off multiple play areas means you’re committing to the ticket longer. You’re more invested in the outcome. You’re hoping for at least one win to validate your purchase. By the time you’ve scratched everything, you’ve mentally invested in the game beyond just the financial aspect. There’s an emotional element now.

Why the Big Prize Jackpots Are Actually the Problem

Every scratch card game prominently displays the maximum jackpot on the front. “Win up to $1,000,000!” is printed right there in bold letters. That’s the psychological hook. Players don’t spend much time thinking about the baseline odds or the structure of smaller wins. They’re thinking about that million dollars.

Here’s what states know: the big prizes drive demand, even though statistically, they’re irrelevant for 99.9% of players.

Let me break down a typical scratch card game. Say it’s a $5 ticket with the following structure:

- 100,000,000 tickets printed

- Payout percentage: 40%

- Total prize pool: $200 million

- Maximum jackpot: $250,000

Now, here’s the magic of lottery math. That $250,000 grand prize? There might be only 2-4 of them in the entire print run. Your chance of winning it is somewhere around 1 in 25 million to 1 in 50 million. You have a better chance of being struck by lightning twice.

But because that prize exists, the lottery can advertise it. And because it exists, players imagine themselves as the winner. They don’t calculate the probability. They just think, “Someone has to win it. Why not me?”

Meanwhile, the prize structure might look something like this: 40% of tickets win something, but most of those wins are $2 or $5 payouts on a $5 ticket. So you’re getting back a fraction of what you spent. The system is designed so that players get frequent small wins to keep them engaged, but the aggregate result is massive money flow to the state.

I’ve seen research from behavioral economists on this, and it’s fascinating. When players win $2 back on a $5 ticket, their brain registers it as a “win” even though they’ve actually lost $3. They don’t always cash out immediately. They often use that $2 to buy another ticket. The states are counting on this. They structure the games so that average players are constantly re-investing their small wins, essentially playing with house money while still giving away more than they receive.

The bigger issue is that most players don’t understand the distribution of prizes. They see the maximum prize and assume there’s a reasonable chance of winning something in that ballpark. In reality, the prize distribution is heavily weighted toward small payouts. You might have 40% of tickets winning something, but maybe only 0.1% winning anything over $50, and maybe only 0.001% winning anything over $1,000.

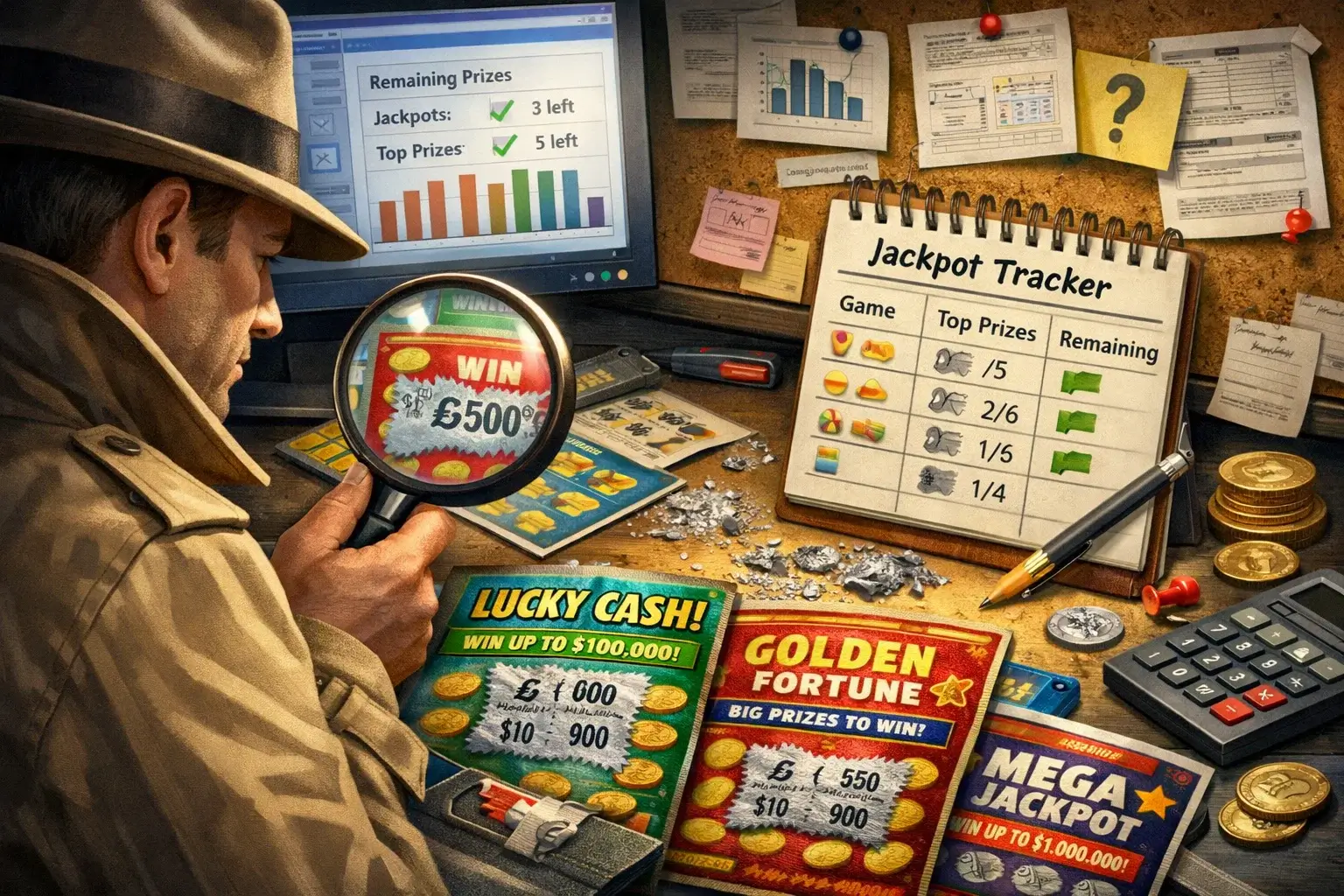

States publish this information technically—you can find the odds on lottery websites. But they’re buried in fine print that nobody reads. The marketing emphasizes the big prizes. The ticket itself highlights the big prizes. The entire psychological apparatus is designed to make you think about the million dollars, not the statistical reality that you’re probably winning $2 or $5 if you win anything at all.

What’s particularly clever is how states use past winners to perpetuate the illusion. They announce when someone wins the big jackpot, they might even feature that person on advertisements, and suddenly the game feels validated. Someone won the million dollars, so maybe you could too. What the lottery doesn’t tell you is that when they found that one winner, there were 50 million other people who didn’t. The ads never show the countless losing players. They show the one person out of millions who got lucky.

The Demographics of Desperation

Here’s where the system gets genuinely depressing. Scratch cards aren’t randomly distributed across income levels. They’re targeted, consciously or not, at people who can least afford to lose money.

I’ve read studies from the University of Massachusetts showing that people earning less than $20,000 annually spend an average of $500 per year on lottery tickets. That’s 2.5% of their income. Meanwhile, people earning over $100,000 annually spend about $100 per year on lotteries. They’ve got better financial options.

Why is this? It’s not because poor people are dumber about math. It’s because the calculation is different when you’re broke. If you’re struggling to pay rent, the idea of a $50,000 jackpot isn’t about greed. It’s about survival. It’s literally the only way you can imagine your situation changing quickly enough to matter.

States know this. They’re not stupid. Lottery commissions employ statisticians, psychologists, and marketing experts. They know exactly who’s buying their tickets. And they’ve designed the entire system to be maximally appealing to people with the fewest resources.

The locations where scratch cards are sold aren’t random either. They’re stocked heavily in convenience stores in lower-income neighborhoods. They’re promoted through advertising campaigns that emphasize quick wins and life-changing jackpots. The messaging isn’t directed at accountants and engineers. It’s directed at people who are looking for any possible edge.

And here’s the thing that really bothers me: states openly acknowledge that lottery revenue is disproportionately generated by lower-income households, but they market it as a benefit. “Our lottery funds education!” they say. Well, technically yes, but the money funding education is coming from people who can least afford it. It’s regressive taxation dressed up as entertainment. A wealthy person loses $100 on lottery tickets and doesn’t notice. A poor person loses $500 and it affects their ability to pay for food or medicine.

The targeting goes deeper than just retail location and advertising. Scratch cards are designed with themes and imagery that appeal to different demographics. You’ve got cards themed around sports, music, instant cash, luxury goods, all carefully crafted to resonate with specific population segments. The companies doing this research understand consumer psychology better than most Fortune 500 companies. They’re not trying to make gambling fun for everyone equally. They’re specifically trying to maximize spending among demographics that have money to lose.

How States Manipulate Odds Through Timing and Distribution

Another thing that people don’t realize is that states can control the distribution of winning tickets over time. Technically, all the winning tickets are in circulation from the moment production begins. But in practice, states manage when and where certain tickets are distributed to maximize revenue.

If a game isn’t selling well, lottery officials can adjust which convenience stores get resupply first, or they can run marketing campaigns emphasizing recent big wins. Conversely, if a game is selling too well, they might slow distribution to stretch out the launch period and maximize the revenue window.

This isn’t some conspiracy theory. It’s public record. Lottery commissions publish data on prize distribution by retailer, and if you dig into it, you can see clear patterns of manipulation.

I’ve also seen states adjust the appearance of games without changing the odds. A redesigned scratch card with new graphics or a different theme might have identical math underneath, but the visual refresh gets people excited again. It’s a relaunch of a game that was selling poorly, but players don’t know the odds were never in their favor in the first place.

There’s also something called “roll-down” in some games, where if a jackpot doesn’t get won in a certain time period, the money gets redistributed to lower prize tiers. This is presented as a good thing for players, but it’s actually another way states control the game. They’re managing the prize pool in real-time based on sales data.

The timing of big winners is particularly strategic. When a state knows a game’s sales are slowing, suddenly a big winner gets announced. Maybe someone won the $100,000 prize in this convenient store over here. Suddenly people think, “The game is still producing winners. Maybe I should buy some.” Sales spike temporarily. States don’t advertise when a game has run without a major winner for weeks. They don’t announce when the expected payout actually occurred ahead of the lottery commission’s profit schedule.

Another manipulation tactic involves the ratio of tickets printed to actual numbers. A state might print 100 million tickets for a game, but make it so there are only 30 million unique number combinations. That means some winning number combinations appear on multiple tickets. The state controls this precisely. They can increase the odds of common prizes and decrease the odds of rare ones without changing the payout percentage by one dollar. Players never know because they’re not analyzing the underlying mathematics of the system.

The Math That Actually Matters: Expected Value

Let’s talk about expected value, because this is the calculation that should matter most to anyone thinking about buying a scratch card.

Expected value is simple: it’s the average amount you’ll win or lose per play over a large number of plays. Here’s how to calculate it.

Take a $5 scratch card with a 30% payout rate. On average, for every five tickets you buy, you’ll get $3 back. That’s a loss of $2 per ticket. A loss of $2 per $5 spent means an expected value of negative 40%.

In casino terms, this is a 40% house edge. No legitimate casino offers anything remotely close to this. It would be embarrassing. But lottery games offer it every day, all day, and millions of people play.

Here’s the problem with expected value calculations, though: they only matter over large sample sizes. If you buy one ticket and win $50, your expected value for that transaction is irrelevant. You won money. Over 1,000 tickets? The expected value math will dominate the actual results. You’ll be close to negative 40%.

This is where the human brain fails us. We have this cognitive bias called the “illusion of control” where we think that playing strategically somehow changes our odds. Some people spend time selecting “lucky numbers” or choosing scratch cards based on when they were printed. None of this matters. Every ticket’s probability is fixed at the moment it’s produced.

Let me give you a concrete example. Say you’re someone who spends $20 per week on scratch cards. That’s roughly $1,040 per year. With a 30% payout rate, you’d expect to get about $312 back. That means you’re losing $728 annually. Over ten years, that’s $7,280 lost. A car. A semester of college. A vacation. Gone.

And this isn’t theoretical. I’ve done the math with actual lottery data. Someone playing $20 weekly on 40% payout scratch games would lose about $936 per year. It’s not a small amount of money. It’s significant. But because the losses are spread across 52 weeks in small increments, people don’t perceive it as significant.

The big insight is this: if you’re spending money on scratch cards expecting to come out ahead, you’re not making an investment. You’re making a donation to your state government. And states count on the fact that enough people don’t understand this distinction. They count on people not doing the math. They count on the psychological tricks overriding the mathematical reality.

Why The Addiction Problem Is Real (And Designed That Way)

I want to be careful not to sound preachy here, but there’s legitimate research showing that scratch cards have a higher addiction potential than many people realize.

A study from the journal Frontiers in Psychiatry found that instant lottery games like scratch cards have faster play cycles and more immediate reinforcement than other gambling forms. This combination is psychologically addictive. You buy a card, scratch it, find out immediately if you won, and decide within seconds whether to buy another.

This rapid feedback loop is intentional. It’s the same reason slot machines are designed the way they are. The faster the play cycle, the more times you play per hour, the more money flows to the house.

I’ve talked to people who have genuine scratch card addictions. And when you dig into their spending patterns, you see something consistent: they started small. A couple of dollars here and there. Then it became a weekly ritual. Then a daily one. Before they knew it, they were spending hundreds of dollars monthly.

The brain’s reward system isn’t calibrated for this. When you win $5 on a $5 ticket, your brain gets a hit of dopamine just like when you win $50. The amount doesn’t matter for psychological purposes. What matters is that you got a win. So the frequent small wins that scratch cards are designed to deliver are actually perfect for conditioning your brain to keep playing.

States know this too. They’ve gotten better in recent years about including responsible gambling messaging on tickets and in advertising. But the underlying game design is still built to maximize play frequency, not to encourage healthy habits.

What’s important to understand is that addiction to scratch cards isn’t a moral failing. It’s a predictable result of good game design. If a product is deliberately engineered to create psychological dependency, then some percentage of users will become dependent. It’s not a bug, it’s a feature from the state’s perspective. That addiction generates millions in revenue. The responsible gambling messaging is there to provide legal cover, not to actually reduce play frequency among vulnerable populations.

The mechanism is simple: variable ratio reinforcement. That’s fancy psychology speak for “you don’t know when you’re going to win, but you know you might win.” Slot machines operate on the same principle, and they’re known to be highly addictive. Scratch cards are essentially the instant-gratification version of slot machines. Same psychology, faster cycle.

The Bottom Line: The House Doesn’t Just Win, It’s Rigged From the Start

I’ve done the research, crunched the numbers, and the conclusion is unavoidable. Scratch cards are one of the most unfavorable gambling products available to consumers. The house edge is massive. The game is designed to exploit psychological vulnerabilities. The distribution is targeted at people who can least afford losses.

This isn’t about judgment. If you buy a scratch card for fun, knowing it’s a $5 entertainment expense you’re comfortable losing, that’s your choice. But if you’re buying them hoping to make money or to change your financial situation, you need to understand what’s actually happening. You’re funding state budgets through a mechanism designed to be mathematically unfavorable to you.

The states win because they control the odds, they control the psychology, and they control how the money flows. It’s not luck. It’s not chance. It’s math, and the math is locked in before you ever hand over your money.

The disturbing part is how openly states run this system. They’re transparent about payout percentages on their websites. The problem is, most people don’t check. States count on this. They’ve created a system where the math is publicly available, but the psychology overrides the math for the vast majority of players.

What would change this? The answer is probably nothing, because scratch cards are too profitable. States are addicted to lottery revenue. In many states, the lottery generates billions in revenue that funds education, infrastructure, and other programs. Taking away scratch cards would mean finding alternative revenue sources, which is politically unpopular. So the system continues, unchanged and largely unchallenged.

Stop thinking about scratch cards as gambling. Think of them as a very expensive tax on people who don’t understand probability. And if you’re paying that tax, at least do it with your eyes open. Understand what you’re actually buying. You’re not buying a chance to win money. You’re buying a 70% chance to donate your money to your state government. You’re buying dopamine hits at a ratio of maybe 30 cents for every dollar you spend.

That might be worth it to you. That’s your choice. But make that choice with full knowledge of the mathematics, the psychology, and the targeting. Make that choice understanding that states have spent decades perfecting the art of extracting money from people who can least afford it. And if you’re spending more than a few dollars a month on scratch cards, be honest with yourself about whether this is actually entertainment or whether it’s something more. Because the design of these games makes the line between the two very, very blurry.